5. What is your context? What are your issues?

Time to share

Write a blog post that briefly describes the higher education teaching context that will form the basis for your inquiry into learning and teaching in this course. Include in that blog post a quick list of the issues around learning and teaching that you are currently aware of within that context and discipline.

(Note: this is not for assessment. Don't spend a lot of time crafting for formal academic writing, feel free to write to think. You will build on this initial contribution as the semester progresses)

Share a link to that blog post in this discussion forum.

When you can, check out the posts shared by the other participants in the course. I've already shared my example.

But I'm not teaching in a higher education context?

If you are not yet teaching in a higher education context, our assumption is that you will develop an “imaginary” context based on a mixture of your disciplinary expertise, your prior experience, and your imagination.

For example, if I were completing a PhD in computer science at a particular university, but not yet teaching full-time. I might imagine I’d just landed a full-time academic job at my current university and identify a particular set of courses I’ve been “allocated” to teach. The advantage of this approach is that I would know a lot of the detail about the context, the learners, the courses etc.

Questions: If you are in this situation and have any questions, please raise them with the teaching team.

Types and elements of reflection

Table of Contents

- Experiencing - Initiation - what issues might drive teacher inquiry into student learning?

- Examining - Types and elements of reflection

- Explaining - Initiation, assumptions and some useful lenses

- Applying - What are the issues and assumptions in your discipline?

1. Introduction

Last week's learning path tried to establish how important reflection is to the act of becoming a Master teacher. It also offered some early explanations of how this course has been designed to enable and require reflection.

Reflection is a complex process. There has been a great deal of literature and advice written about what reflection is, how it should be done, how it can be measured, its limitations etc. Some of what's been written can be incredibly complex to understand.

This book introduces the view of reflection that will underpin this course. These are provided here to help scaffold your engagement with the course, rather than position them as the "perfect" take on reflection. The book describes

- different types of reflective writing;

(The rubrics for the course assignments use these types) - elements to be expected within reflective writing; and,

- a process for engaging in critical reflection.

At the end you will be asked to apply some of this to the issues that were shared in the first part of this learning path.

2. A developmental framework of reflection

Hatton & Smith (1995) undertook a process which identified (emphasis added)

four types of writing, three of which were characterised as different kinds of reflection. Defining characteristics for descriptive writing, descriptive reflection, dialogic reflection and critical reflection…. In essence, the first is not reflective at all, but merely reports events or literature. The second, descriptive, does attempt to provide reasons based often on personal judgement or on students' reading of literature. The third form, dialogic, is a form of discourse with one's self, an exploration of possible reasons. The fourth, critical, is defined as involving reason giving for decisions or events which takes account of the broader historical, social, and/or political contexts. (p. 40-41)

It is important to note that these types of reflective writing (descriptive, dialogic and critical) should not be seen as a hierarchy or as exclusionary. i.e. you should not always be aiming to avoid descriptive reflection and always produce critical reflection. Hatton and Smith (1995) identify that it is inevitable that some descriptive writing is necessary to describe the context. Hatton and Smith (1995) end up identifying a developmental framework that sees the individual developing the (emphasis added)

capacity to undertake reflection-in-action, which is conceived of as the most demanding type of reflecting upon one's own practice, calling for the ability to apply, singly or in combination, qualitatively distinctive kinds of reflection (namely technical, descriptive, dialogic, or critical) to a given situation as it is unfolding. In other words, the professional practitioner is able consciously to think about an action as it is taking place, making sense of what is happening and shaping successive practical steps using multiple viewpoints as appropriate. (p. 46)

For the purpose and confines of this course, the focus is just on being aware of the different types of reflection identified by Hatton and Smith (1995)

3. Overview of types of reflection

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Descriptive writing |

|

| Descriptive reflection |

|

| Dialogic reflection |

Demonstrates a "stepping back" from the events/actions leading to a different level of mulling about, discourse with self and exploring the experience, events, and actions using qualities of judgements and possible alternatives for explaining and hypothesising. Such reflection is analytical or/and integrative of factors and perspectives and may recognise inconsistencies in attempting to provide rationales and critique, for example. While I planned to use mainly written text materials I became aware very quickly that a number of students did not respond to these. Thinking about this now there may have been several reasons for this. A number of students, while reasonably proficient in English, even though they had been NESB learners, may still have lacked some confidence in handling the level of language in the text. Alternatively, a number of students may have been visual and tactile learners. In any case I found that I had to employ more concrete activities in my teaching. |

| Critical reflection |

Demonstrates an awareness that actions and events are not only located in, and explicable by, reference to multiple perspectives but are located in, and influenced by multiple historical, and socio-political contexts. For example, What must be recognized, however, is that the issues of student management experienced with this class can only be understood within the wider structural locations of power relationships between teachers and students in schools as social institutions based on the principles of control" (Smith, 1992) |

4. Elements of reflection

As with the types of reflection discussed previously, the elements of reflection on this page are presented as a useful taxonomy to support your reflection during this course and beyond. It is not presented here as the single correct collection of reflection elements. The five elements presented here were identified by Ullmann et al (2012). Ullmann et al’s (2012) five elements of reflection are:

-

Description of an experience.

-

Personal experience.

-

Critical analysis.

-

Taking perspectives into account.

-

An outcome of reflection.

In short, it can be useful to actively try and include these 5 elements in any reflection. Ullman et al (2012) do recognise that these are not necessarily five separate elements, there is overlap. One example is that your description of an experience could include some critical analysis and an attempt to present multiple perspectives.

The following offers a short description of each element. Ullman et al (2012) offer an expanded version in Section 4 of their paper.

4.1. Summary of the elements

Description of experience

What happened? Or perhaps in this course, what did you read, see or listen to?

The idea is to start your reflection by "recalling and detailing the salient moments of the event" (Ullmann et al, 2012, pp. 104). If you're reflecting on something you've read, you might give a brief summary of its main point(s). Or, the points that are most salient to what you’re reflecting upon.

Personal experience

The reflection should include your thoughts and feelings, based on the idea that reflection is a type of inner dialog. It shouldn't just be a summary of what you read or experienced. It should aim to connect that experience with your existing knowledge, thoughts and feelings. It's appropriate to say you didn't understand, you disagreed or that you were confused or made angry. It’s ok to include emotion. Feel free to write it in the first person.

Critical analysis

Description of what happened and your experience is not enough. You have to question your assumptions, values, beliefs and biases. You have to question the assumptions, values, beliefs and biases of what you've experienced, read, seen or listened to. You might analyse, argue, evaluate, synthesise and test these assumptions etc. with other ideas and experiences. Look for inconsistencies, disagreement, commonality, reasons and justification. Think about how you can link and integrate ideas.

Take perspectives into account

How you look at an experience or idea is important. Look to understand the perspective embedded in the experience, idea or yourself. Look for alternatives. Talk with others and see what they are thinking. Different ways of looking at a problem can reveal new ideas. This is also where different theoretical and conceptual models can offer assistance.

An outcome

Did you develop a new understanding through this process? Did you experience transformative learning? Or, did the experience confirm you existing understandings? What will you do know with this?

Summarise what you learned, offer some conclusions and make plans for how you will use this into the future. Does it link to a particular assessment task? Is there something further you need to read or think about? Change a teaching practice?

5. Assumptions

In describing the TISL heart model for teacher inquiry, Hansen and Wasson (2016) offer the following experience

After reviewing the Post-it notes together with the teachers, the discussions revealed that they tend to ‘jump’ to the research question when explaining their assumptions. The idea of the assumption step was to get the teachers to think about their kick-off issue and identify the beliefs they have about this issue.

Given how the human mind works, it is no surprise that our assumptions take over. As identified by Hansen and Wasson (2016) it is important that we question our assumptions before going too far.

How do you do that?

Brookfield (2009) suggests that (emphasis added)

Reflection focuses on uncovering assumptions, the conceptual glue that holds our perspectives, meaning schemes and habits of mind in place. People’s capacity for holding assumptions that contradict each other, and that are contradicted by events and experiences, knows no bounds. As Basseches (2005) illustrates, adults are able to move back and forth between asserting general assumptions that are viewed as guides for living (such as honesty is the best policy) and particular, context-specific assumptions that contradict the general ones (sometimes circumstances mean that lying about one’s real agenda or motivation is necessary for one to have any chance of success). The texts of our lives our experiences and how we ascribe meaning to these are the focus of assumption hunting. The internal grammar of these texts comprises the assumptions, and ways we assess the accuracy of these, that we develop to explain situations, solve problems and guide actions. We develop assumptions about the meaning that should be ascribed to other people’s words, assumptions about the significance of others’ behaviours, assumptions about how to solve problems we keep encountering, and assumptions to guide our choices, judgments and decisions. Conceived this way critical reflection involves us recognising and researching the assumptions that undergird our thoughts and actions within relationships, at work, in community involvements, in avocational pursuits and as citizens. It takes the process outside the classroom and away from academic disciplines and divisions and places it squarely in the centre of our experiences (p. 294-295)

Even becoming aware of your assumptions is hard.

The critical analysis and other assumptions elements from Ullman et al (2012) are steps intended to help uncover, question and test assumptions. But how to do it?

5.1. Three types of assumptions

Brookfield (2017) identifies three broad categories of assumptions: paradigmatic, prescriptive and causal. While at USQ, you should be able to read more about these via this online version of Brookfield (2017).

Note: To read the online version of Brookfield (2017) you will likely need to create an account on the Proquest service. Use your USQ student email address.

Looking for assumption examples

Read the Types of Assumptions section from Brookfield (2017).

Return to one of the issues raised earlier in this learning path. Your choice, it can be an issue you raised or one from elsewhere. Also feel free to think of examples from your own practice.

Identify examples of some of the paradigmatic, prescriptive and causal assumptions that apparently inform that particular issue and how it is conceptualised.

Feel free to mention some of the assumptions mentioned by Brookfield.

For example

Causal assumption

Brookfield (2017) lists the following causal assumption of his

Making mistakes in front of students creates a trustful environment for learning in which students feel free to make errors with less fear of censure or embarrassment.

On a somewhat related note, I believe that sharing the evolution of my thinking around the ramble/learning path increases teacher presence, models practice, and shows a willingness to show my "writing to think". My assumption/hope is that this will help improve your learning and also help address somewhat the feelings of vulnerability when students are asked to reveal their thinking through reflection.

Prescriptive assumptions

Underpinning the whole design of this course is the prescriptive assumption that tertiary teachers should engage in reflection and inquiry into student learning to become master teachers. And, there are many, many more.

Paradigmatic assumptions

In terms of issues for higher education, Goodyear (2015) identified this issue

Employers and their representatives are continuing to criticise universities for failing to produce work-ready graduates. Students themselves are questioning whether they are getting a fair return on the time and fees they are investing.

A paradigmatic assumption underpinning this issue is that the role of the University is to produce work-ready graduates. To help students get a job. Some argue that this represents a broader paradigmatic shift within society, a shift that many are unhappy with. It's an assumption that has not always held for universities.

6. One process for critical reflection

The following is just on set of steps you might use to move into identify, question and test your assumptions. It is not held up as perfect, it is suggested as useful. It has been distilled from the work of Brookfield and others, including the aspects summarised on this “How to be critical when reflecting on your teaching?” page.

The process

-

Start by describing the experience and your personal experience.

i.e. create the first two elements of the list of elements of reflection from Ullman et al (2012). -

For each of Brookfield's (2017) three types of assumptions - causal, prescriptive and paradigmatic - repeat the following steps

- Analyse your description for examples of the current type of assumption.

- Why do you believe this?

Is there theory or literature that supports this causal assumption? Or is this just an assumption that you have, or which is prevalent in the context. What evidence do you have of this causal connection? Can you explicitly lay out the rationale for each causal assumption?

Perhaps make use of the 5 Whys technique. -

Ask others for alternate explanations.

Provide some or all of your causal assumptions to others and invite them to offer their perspective. Especially if there is someone you know who will disagree. (Note: the aim isn’t necessarily to disprove your assumptions. Initially, the aim is to simply to make you aware of different explanations to consider).

Brookfield (2017) suggests the use of four lenses, including : students’ eyes and colleagues’ perceptions. What explanations might your students’ offer? Don’t forget that different students might offer different explanations and it is unlikely that any of them will match your assumptions. -

Look for literature as a source of alternate explanations.

The words “theoretically-informed” is mentioned a number of times in the specification for this course. Relevant scholarly literature can provide findings and theories that offer alternate assumptions. -

Skeptically imagine other explanations.

Draw on any of the alternate explanations you’ve uncovered and re-examine the experience. Replace all your assumptions with the alternate explanations. What does this reveal?

Initiation, assumptions and some useful lenses

Table of Contents

- Experiencing - Initiation - what issues might drive teacher inquiry into student learning?

- Examining - Types and elements of reflection

- Explaining - Initiation, assumptions and some useful lenses

- Applying - What are the issues and assumptions in your discipline?

1. Introduction

The task

As mentioned earlier, the aim this week is for you to start thinking about the first stages of your inquiry into learning and teaching. The initiation of kick-off stage has been described this way

A possible scenario for the integrated model follows Carla, a chemistry and mathematics teacher in an Upper secondary school. Her analysis of students’ assessment last year suggested some common misconceptions in the understanding of converging series. This year she decided to inquire this problem more thoroughly. She consults the integrated model to plan her teacher research project. The Initiation was her realization of the students’ misconceptions. (Emin-Martinez et al, 2014, p. 8)

the Kick-off, which is when a teacher first identifies the issues related to student learning in which s/he is interested (Hansen and Wasson, 2016, p. 39)

Identify something you would like to know about student learning? Something you wonder about? E.g., Why are some of the students not learning the material? What do the students think about my new learning materials? (Hansen and Wasson, 2016, p. 44)

The problem

But as mentioned before our assumptions limit how we think about these issues, Hansen and Wasson (2016) again

After reviewing the Post-it notes together with the teachers, the discussions revealed that they tend to ‘jump’ to the research question when explaining their assumptions. The idea of the assumption step was to get the teachers to think about their kick-off issue and identify the beliefs they have about this issue. (p. 43)

The solution

The previous book in this learning path suggested a process of critical reflection as a way to identify and question assumptions. One of the steps in that process the use of literature and included the suggestion that "relevant scholarly literature can provide findings and theories that offer alternate assumptions".

This book introduces three different lenses from the scholarly literature as examples.

2. On Theory

If your background is not within education, then educational theory can be a deep and frightening forest to navigate. The following provides one specific "map" to understanding what educational theory is and why we use it.

Hirst (2012) describes educational theory as

A domain of practical theory, concerned with formulating and justifying principles of action for a range of practical activities. (p. 3)

i.e. educational theory should help you teach and help your learners learn. It can help you identify reasons why you should (or shouldn't) use different practices.

Why use theories?

Thomas (1997) cites Mouly (1978)

Theory is a convenience a necessity, really organizing a whole slough of facts, laws, concepts, constructs, principles into a meaningful and manageable form (p. 78)

These theories are useful because they help you understand, formulate and justify how and what to do. Learning, teaching is difficult Theories should help you make sense of this complexity. Guide you in understanding, planning, implementing and evaluating of your use of ICTs. Theories provide you knowledge.

Bates (2015)

With a knowledge of alternative theoretical approaches, teachers and instructors are in a better position to make choices about how to approach their teaching in ways that will best fit the perceived needs of their students, within the very many different learning contexts that teachers and instructors face (pp. 44-45)

Right now, we're interested in using educational theory as a lens to surface your assumptions and provide alternate assumptions as a way to understand issues you might like to explore more.

3. Three lenses to surface assumptions

The following introduces three different lenses (theories, frameworks, models etc) and suggests that they can be useful for identifying ways of looking at learning and teaching (assumptions). These are by no means the only three, or even the most useful three. (the most useful would be very contextual).

Put these lenses on

Reading about these lenses is not sufficient, instead we suggest that you:

- Select a particular context and related issue(s).

The best choice would be the context and issues you shared earlier in this learning path.

- Use one or more of the following lenses to identify different assumptions for some of the issues.

- Write a blog post that summarises what you've come up with.

- Post a link to this blog post in this discussion forum.

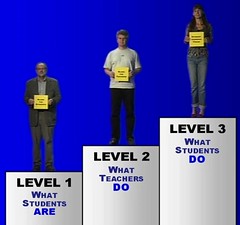

3.1. Constructive alignment and 3 levels of teaching

Constructive alignment is an idea from Biggs (2003) that is in widespread use across higher education. Backward design is another related idea.

Teaching Teaching & Understanding Understanding is a short (19 minutes) film produced to explain the major ideas within constructive alignment. Biggs (2012) is a journal paper that offers an overview of the same. Rather than focus on all of the ideas underpinning constructive alignment, the focus here will be on the three levels of teaching proposed as part of constructive alignment and summarised in the image to the right taken from the "teaching teaching" short film.

The idea is that these levels each represent a particular set of assumptions that guide how teachers teach.

Level 1 - What students are

The assumption what the students are (and the differences between them) are the most important influence on student outcomes. The job of the teacher is deliver the information, the job of the students is to engage with it, and if a student can't, then it's their fault. The problem can't have been with the teaching, the information was transmitted effectively.

Level 2 - What teachers do

The assumption here is that improvements in student learning outcomes can be achieved by improving how the teacher transmits the information. i.e. the behaviour and tactics adopted by the teacher can improve student learning. Biggs (2012) gives the following as examples of the types of prescriptive advice given to teachers at this level

- establish clear procedural rules at the outset, such as signals for silence;

- ensure clarity: project the voice, clear visual aids;

- eye-contact students while talking;

- don’t interrupt a large lecture with handouts: chaos is likely

This advice, useful as it is, is concerned with management, not with facilitating learning. Good management is important for setting the stage for good learning to take place – not as an end in itself. (p. 44)

Level 3 - What students do

Hopefully you realise that this is seen as the "good" level. This level is based on the assumption that student learning can only arise from what the student does. Biggs (2012) quotes Shuell (1986)

If students are to learn desired outcomes in a reasonably effective manner, then the teacher’s fundamental task is to get students to engage in learning activities that are likely to result in their achieving those outcomes. . . . It is helpful to remember that what the student does is actually more important in determining what is learned than what the teacher does (p. 429).

3 levels of teaching and the teacher behaviours checklist?

In the first learning path for this course you completed a survey and learned about the Teachers Behaviour Checklist (TBC).

In which of Biggs three levels of teaching do you think the TBC might fit? What might this say about the limitations and applicability of findings from the TBC?

3.2. Categories of teaching experience and practice

Tutty et al (2008) identified five different categories of how computing academics experienced teaching in tertiary education. Those categories are then mapped against five dimensions and summarised in a table (Tutty et al, 2008, p. 180) on which the following table below is adapted.

Where do you fit?

Ignore the left-hand column of the table below.

For each of the other columns, identify which cell resonates with how you think you (would) perceive or experience teaching. (Taking into account that you may not be a computing academic)

| Category | Focus: extent to which the teacher aims to prepare the students | Curriculum: teacher’s approach to development and provision of teaching material | Learners: teacher’s view of their students as learners | Collaboration: how the teacher works with others | Community: who the teacher works with |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher as the isolated authority delivering a subject | Subject: the content of this subject | Conservatism: reuse existing materials and little consideration given to appropriate use of technology | A homogenous group of learners | Individualistic: limited or no collaboration with others | Individualistic: limited or no communication with others |

| Teacher as the authority delivering course | Degree course: the necessary knowledge and skills to progress through the course | Adequacy: updates material and technology to meet curriculum objectives | A group with different levels of knowledge | Directive: communication is from leader to team | Local: discusses teaching matters with teaching group |

| Teacher as the facilitator of students’ learning | Employment: preparing students for the workforce | Relevancy: update regularly for currency and to reflect current best IT practice | Individuals with their own learning characteristics | Consultative: communication is from leader to team but feedback is highly valued | Local: discusses teaching matters with other colleagues in the university |

| Teacher as a facilitator of a learner-centred environment | Career: preparing students for lifelong work in a range of careers and workplaces | Relevancy: update regularly for currency and to reflect current good IT practice | Individuals who need to interact, negotiate and engage with the material and others | Collaborative: works with others to teach the subject | External: discusses with people outside he university |

| Teacher as a member of a learning community | Life and society: understanding the role of IT in society and its influences on all aspects of life | Innovation: updates for immediacy and is an early adopter of state-of-the-art IT | Individuals actively creating their own learning as they become life-long learners | Collaborative: works with others to teach the subject | External: discusses with people outside the university |

3.3. Pedagogical models & their use in e-learning

Conole (2010) aims to provide

a review of pedagogical models and frameworks, focusing on those that are being used most extensively in an e-learning context (p. 2)

To achieve this she uses an overview of learning theories and then maps against those theories a range of mediating artefacts. Pedagogical models and frameworks are one type of mediating artefact that is mentioned. All of this is summarised in a table upon which the following table has been based.

The emphasis in the table below is meant to represent my understanding of the models and learning theories that have informed the design of this course.

Where does your approach fit?

Examine the table below. Are you able to identify the examples and spaces that best capture your approach to teaching?

If so, are you happy with where it is? Are there other areas on this table that appeal?

If not, why?

| Perspective | Approach | Characteristics | E-learning application | Models and frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Associative |

Behaviourism; Instructional design; Intelligent tutoring; Didactic; E-training |

Focuses on behaviour modification, via stimulus response pairs; Controlled and adaptive response and observable outcomes; Learning through association and reinforcement |

Content delivery plus interactivity linked directly to assessment and feedback |

|

|

Cognitive |

Constructivism; Constructionism; Reflective; Problem-based learning; Inquiry-learning; Dialogic-learning; Experiential learning |

Learning as transformations in internal cognitive structures; Learners build own mental structures; Task-orientated, self-directed activities; Language as a tool for joint construction of knowledge; Learning as the transformation of experience into knowledge, skill, attitudes, and values emotions. |

Development of intelligent learning systems & personalised agents; Structured learning environments (simulated worlds); Support systems that guide users; Access to resources and expertise to develop more engaging active, authentic learning environments; Asynchronous and synchronous tools offer potential for richer forms of dialogue/interaction; Use of archive resources for vicarious learning; |

|

|

Situative |

Cognitive apprenticeship; Case-based learning; Scenario-based learning; Vicarious learning; Collaborative learning; Social constructionism |

Take social interactions into account; Learning as social participation; Within a wider socio-cultural context of rules and community; |

New forms of distribution archiving and retrieval offer potential for shared knowledge banks; Adaptation in response to both discursive and active feedback; Emphasis on social learning & communication/collaboration; Access to expertise; Potential for new forms of communities of practice or enhancing existing communities |

|

| Assessment |

|

|||

| Generic |

|

|||

What are the issues and assumptions in your discipline?

Table of Contents

- Experiencing - Initiation - what issues might drive teacher inquiry into student learning?

- Examining - Types and elements of reflection

- Explaining - Initiation, assumptions and some useful lenses

- Applying - What are the issues and assumptions in your discipline?

1. Introduction

This learning path was designed to get you started on your journey into inquiring into learning and teaching within your context. To this end you have so far:

-

Looked at some of the types of issues that other teachers have been interested in.

-

Been introduced and asked to start applying some specific ideas about reflection, especially in terms of surfacing assumptions.

-

Started engaging with different useful lenses for surfacing assumptions around learning and teaching.

The next step this week is to start thinking about the assessment, in particular, to start work on Part A for Assignment 1.

Read about Assignment 1, Part A

Read the description of Assignment 1, Part A. Do you understand what you need to do? If you have any questions, please ask them in the Questions and Discussion forum.

2. Mapping blog posts and assessment tasks

Assignment 1, Part A - like most of the assessment tasks for this course - includes the following requirement (emphasis added)

The critical analysis of your conceptions of good teaching practice will be undertaken through a series of reflections that reflect on and build upon the analysis contained in your personal blog posts from earlier in the semester on assumptions and conceptions of teaching practice

Each of the assessment tasks are directly connected to blog posts that you will be encouraged to “write to think” during the semester. The idea is that by the time you start work on your assessment tasks you should have a small (large?) collection of blog posts to inform your blog post (essay) for each assessment task.

Mapping your progress

One way to ensure you have a collection of blog posts would be to map your “write to think” blog posts against the specific assessment tasks. i.e. have some way you can quickly see how many "write to think" posts you've written for each assessment, so you are aware of your progress.

You could do this manually, or you could make use of software to help.

Blog categories

One approach to doing this is via categories or tags on your blog. These are ways of allocating a blog post to a particular collection. You could have one collection for each assessment task and you could then easily track progress.

If you’re using Wordpress for your blog, then categories can be used to group related posts together.

For example, I use categories on my blog to group posts related to particular courses. For example, all my EDU8702 blog posts (very small number) or all my EDC3100 blog posts (a course I taught for 5 years).

How are you going to map your progress?

How are you going to track how many “writing to think” blog posts you’ve written for each assessment task?

3. Planning for Assignment 1, Part A

Assignment 1, Part A asks you to identify a particular discipline into which you teach. The discipline you choose should be used throughout the course. Subsequent assessment tasks will build on the work you do in Assignment 1, Part A.

Already in this learning path you've been asked to share some details about your teaching context. It's time to start thinking about finalising your context and discipline. You can't make any significant progress on Assignment 1 until you do.

Literature review

You will need to undertake a literature review of the teaching in your discipline. The USQ library offers this advice on writing literature reviews. Based on this advice, consider Assignment 1, Part A at the upper-end of the undergraduate level in terms of the number of references you should look to include.

Start planning

The following questions are offered to get you started on Assignment 1, Part A.

-

What is your teaching discipline?

-

What is your specific context? First year? Second? A particular course or sub-discipline? (e.g. computer programming)

-

Identify what you need to know about teaching in your discipline?

-

Where is the best literature around teaching in your discipline?

-

Are there related disciplines?

-

What are its current and important issues?

-

What is its history? Have there been any evolution in understanding?

-

What are the assumptions underpinning teaching in your discipline?

Start planning out your literature review, examine the above questions, add some more and start thinking about how you’ll go about answering those questions. Write a blog post outlining your plan.